Andaman: The Cellular Jail

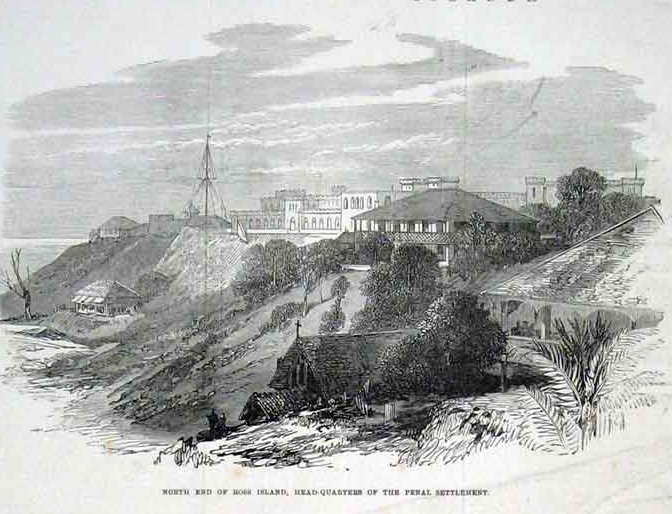

The penal settlement on the Andaman Islands was established successfully on the 10th of March 1858. Attempts to do so once before had failed in 1796. The first ship carrying two hundred prisoners docked at the Chatham Islands. The lack of access to drinking water, however, caused the settlement to move to Viper Island. It was moved to Ross Island and Port Blair within a few years.

On Viper and Ross islands, the penal settlement functioned as an open prison. A thousand convicts were housed in forty huts which lined the principal road running as a North-South corridor through the centre of the Island. Each hut was ten feet by sixty feet and they were built ten feet apart from each other. The bottom floor was used as a kitchen and tool shed while the upper floor was used for sleeping. This was done to protect the convicts from fatal malarial attacks. The constant rainfall, however, dampened their clothes and bedding, leaving them with little protection from mosquitoes within their huts. They were made to clear out the forest, construct buildings and huts for the settlement for nine to ten hours each day. The cuts from poisonous plants and the friction caused by the fetters on their feet resulted in ulcers which, upon not being attended to, would get infected, causing immense pain and often death.

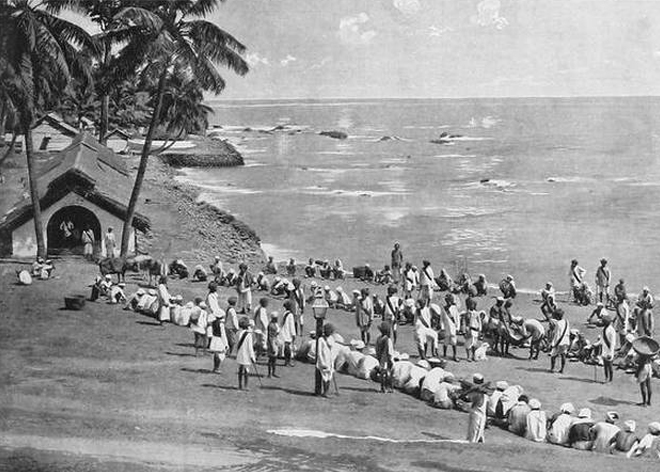

Attempts to escape this internment were recorded as early as the first thirty-six days of the establishment of the settlement. Numerous such attempts dotted the century which would follow but very few convicts would manage to reach the mainland alive. Since October 1858, thirteen thousand thirty convicts had arrived on the archipelago. Within the first year, a hundred and ninety-one had died within the hospital, while a hundred and seventy had fled from the settlement and were unaccounted for. It was assumed that they had been killed by the aborigines or had drowned in the sea.

On the severity of life within the penal settlement, Rev H Corbyn states,” that spirit of the native man was so defeated upon arrival at the settlement, that he would lose all recognition of his self”. A glimmer of hope resided in rumours that a direct land link existed connecting the islands to mainland India. Many convicts escaped from the settlement on foot, determined to find a way back home. These men, however, had fatal ends.

By 1862, the penal settlement, now at Port Blair, comprised of two thousand five hundred convicts. British authorities had been clearing these islands for twenty four years now. The British desired to use convict labour to clear the heavily forested islands in order to access cultivable land and its expected rich mineral resources, a stepping stone towards transforming the island into a prosperous province. In a letter to the Government of India, the Superintendent, Port Blair, Tytler argues that a 7900% increase in internment would be needed to compensate for the high mortality rate of convicts and for the paucity of convict labour within the Andamans.

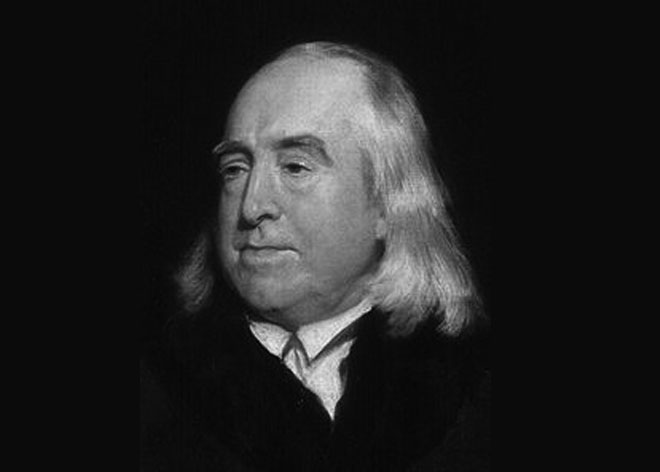

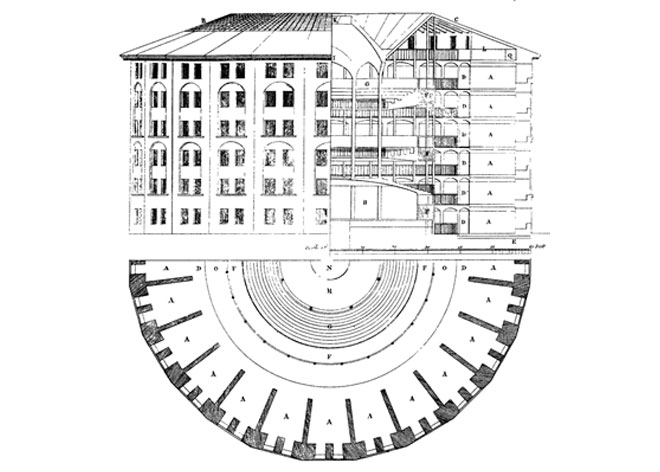

Within thirty years, the British would begin to concentrate their resources on Port Blair towards the construction of a ‘Cellular’ Jail, a large wheel-like construction based on Jeremy Bentham’s concept of Panopticon, a silent system based on the idea of isolation, silence and surveillance.

The Cellular Jail was built for those “whose removal from India was considered in the public interest”. Men, women and children who were convicted to life imprisonment or sentences of more than seven years could be sent to the Islands.

Although the Reformatory Schools Act (1897) prohibited the transportation of convicts younger than the age of fifteen to the Andamans, convicts sentenced to the death penalty or ‘transportation for life’ were considered exceptions. Despite the harrowing conditions of life and labour in the Cellular jail, five boys, aged between fifteen and seventeen were interred there in 1933. The youngest convict was 15-year old Haripada Bhattacharya. The British defended the decision to condemn the boy by stating that he deserved the death penalty for his crime of murdering a police officer in Chittagong. They said it was only his age that convinced the judge to grant him transportation instead.

The Prisons Act (1894) mandated living conditions for the convicts. According to this, separate confinement was the exception at the Cellular Jail, not the norm. However, each convict was allotted a separate cell, that opened to the back of the cells before them. The only other source of light or ventilation was a small window in the back wall of the cell. Convicts were allowed to talk amongst each other in hushed tones after their labour assignments for the day were done. Special care was taken to keep apart convicts who may know each other from before their internment at the Cellular Jail. The sense of isolation was only heightened by the limitations on any communication with the outside world. Only convicts who were considered “suitably behaved” were allowed to write and receive letters or visitors from the mainland. All conversation was monitored closely and no matters of political relevance were allowed to be discussed.

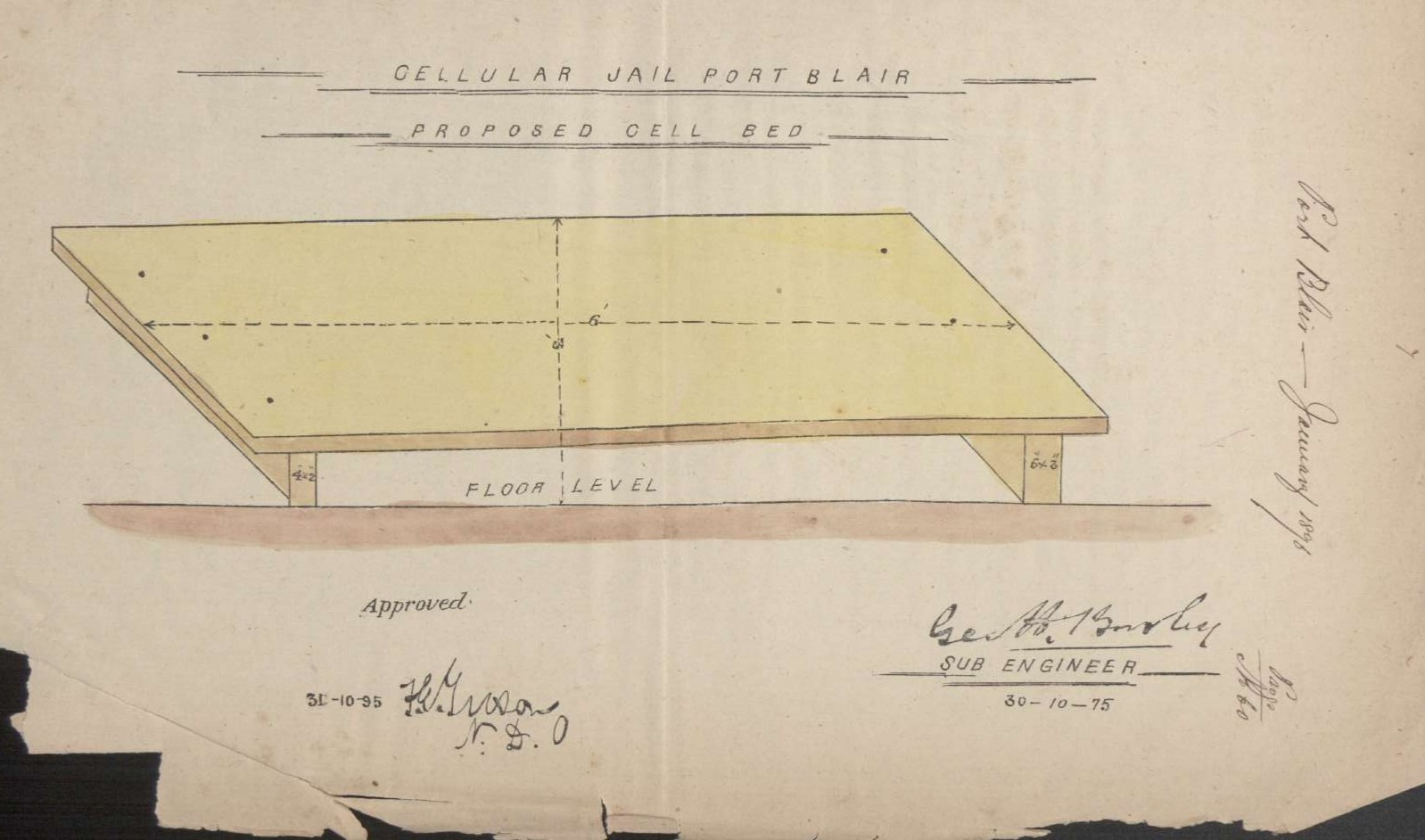

Each cell should have housed a wooden bed, a chair, a small table, a shelf, an earthen water container and a flat bottomed urinal utensil. Each convict should have had received safety razors, Colgate toothpaste and Lifebuoy soap. These were privileges that could be taken away as punishment by the authorities. Male convicts had their hair closely clipped every fifteen days (except in the month before their release) and were clothed in dosuti cotton dhotis or trousers with a kurta or a shirt. All convicts had to wear a two inch square badge on their right shoulder to distinguish themselves from the Convict warders who wore a similar patch on their right arm. All convicts had a wooden placard around their neck which was an identification card. It would have the details such as their provenance and their sentence inscribed onto it.

Every morning the cells would be opened at dawn, a thirty-minute latrine parade followed a quick check by the head warder. The complex contained one bathroom for every six convicts, each convict received five mins, anytime spent in excess of this would need to be subtracted from a fellow convict’s time.

Breakfast should have included buttered bread with tea, Lunch would include rice, dal, vegetables with a side of tamarind or lime, gur and curd. Protein requirements were supposed to be met with meat, fish, eggs or milk in proportional amounts.

The prison should have housed a library. Convicts should have been allowed to issue upto five books at a time and have access to newspapers such as 'The Illustrated Times of India', 'the Sanjibani' and 'the Bangabasi'. The regulations of 1894 also stated that the convicts would not be fettered or whipped except in cases of misbehaviour or to foil an attempted attack on any fellow resident.

However, these regulations would remain only on paper. Three prisoners, Mahavir Singh, Mohan Kishore Namadas and Mohit Moitra, led a hunger strike within the prison in 1933 to address the abysmal living conditions within the jail. Their demands included access to books, soap, edible food and a right to communicate with their fellow inmates. While the three leaders died under mysterious circumstances, the strike continued for forty-five days till the demands were partially fulfilled.

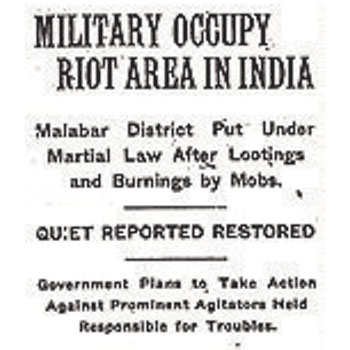

Growing opposition to the conditions within the Cellular jail had pressured the Government to initiate the process of shutting the jail down. By 1921, local governments were asked to take steps towards the halting of deportation to the Andamans, as far as possible. All but three provinces complied. Punjab, the North-West Frontier Province and Madras, however, were recovering from the repercussions of the Khilafat Movement and the Mapilla Rebellion. The ‘terrorists’ convicted of participating in these agitations continued to be sent to the Islands. In 1921, fourteen thousand Mapilla rebels were transported to Port Blair. The prisoners already inside the jail were kept there for the remainder of their sentences due to a paucity of jail accommodation within mainland jails. By 1931 all “troublesome habituals or violent convicts’’ were repatriated. Punjab would cease transportation only in 1932.

By the 1930s, the policy of the Government of India as to the future of the Andamans became to abandon the island as a penal settlement and to convert it into a self-supporting community. The islands were opened to ‘self-supporting’ ex-convicts and volunteers by the Indian Jails Committee report. Cellular jail convicts who chose to settle down on the islands would qualify for a reduction of a third of their sentence while convicts in jails on mainland India would qualify if they were aged between eighteen and thirty-five years and would be less than fifty-five years upon the date of their release.

During the Second World War, the Andaman Islands were occupied by the Japanese army. They handed over its administration to Subhas Chandra Bose and the Azad Hind Fauj. During this occupation, the Japanese would empty the Cellular jail and destroy three wings of the Jail to build barracks for their army. Another two wings would be pulled down due to structural damages.

The defeat of the Axis powers led to the return of these islands to the British. In 1947, the Indian Government assumed control of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands permanently.

On 30th December 2018, Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi renamed the Ross Island as Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Dweep, the Neil Island as Shaheed Dweep and the Havelock Island as Swaraj Dweep.

Government of Indiaa

Government of Indiaa

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.