The Darjeeling Himalayan Railways: A Passage through Time

During the 19th century, till the time the Northern Bengal State Railway extended its operation to Siliguri in 1879, the journey from Calcutta to Darjeeling was a daunting one.

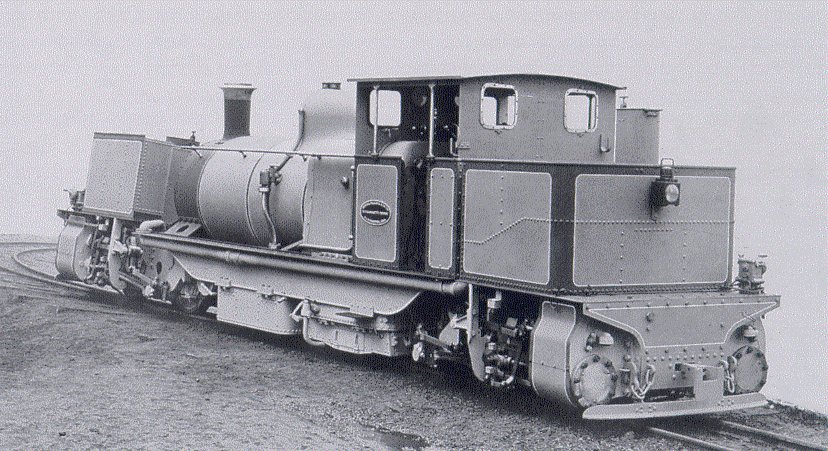

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, Steam Engine. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

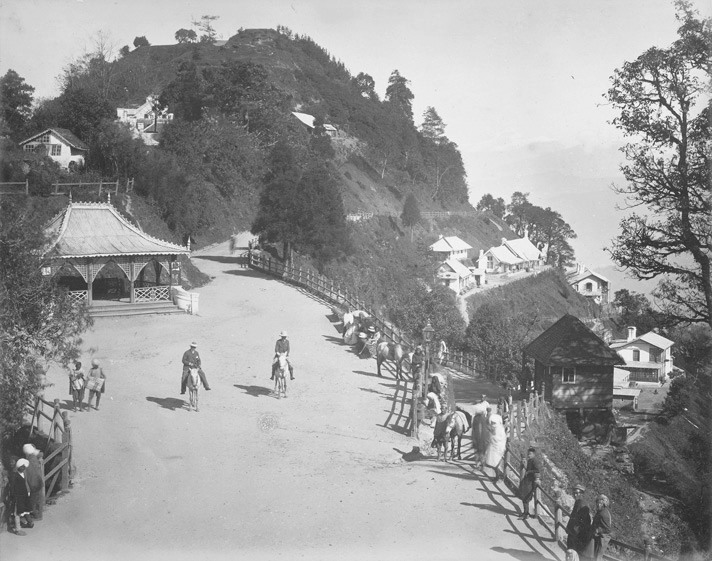

Various means of transport including rail, steam ferry, bullock cart and the road were employed to reach Darjeeling. The journey took five to six days. The railway was considered to be a panacea to the problems presented by conveyance through the Hill Cart Road where, for years, travellers had used pack ponies, bullocks, palkees (palanquins), pony tongas (horse-drawn carriage) and bullock carts to reach their destination. Tea and other local produce from the Darjeeling hills could now be easily transported to the plains and likewise necessary supplies, tea garden machinery and troops could be sent to the hills in a timely fashion. Siliguri, located at the foothills of the Himalayas, 400 feet above sea level, became the point at which the travellers would have breakfast served to them in the morning, after an unbroken rail journey from Sara Ghat. From there the travellers would transfer from a metre gauge system to one where the rails were only 2 feet apart and the entire journey would now take less than 24 hours.

A Darjeeling Street in the 1880s. Source: Wikimedia Commons

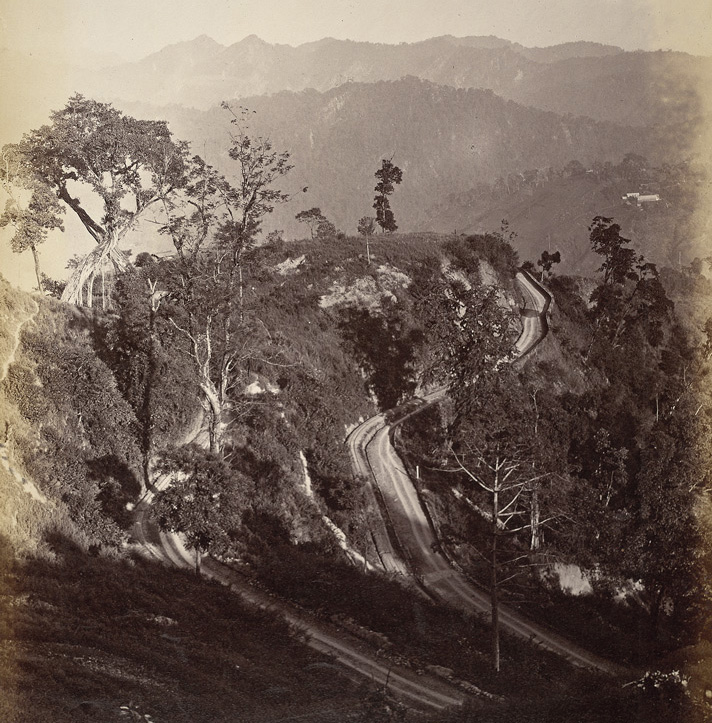

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway Tracks in the 1890s. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The onward journey would be carried forth on the miniature trains of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. Travellers would marvel at its tiny scale, its tracks laid out like something out of a toy train set box. Despite its quaint features the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, also known as the Toy Train, was a formidable engineering marvel. It was built between 1871 and 1881.

The origin of the Toy Train was tied to the construction of the Hill Cart Road which was started in 1839 under Lieutenant Napier of the Royal Engineers who had been deputed to lay out the town of Darjeeling. This strip of hill territory which had earlier been part of the Kingdom of Sikkim became part of British India in 1835. As the hill station expanded, the old cart road now known as the Old Military Road was found unsuitable and a new Cart Road was sanctioned in 1861. This new road connecting Siliguri to Darjeeling became the route through which the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway made its way slowly from the foothills, navigating the numerous spurs to its final terminus at Darjeeling.

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, Class D locomotive. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway tracks along the Hill Cart Road. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The plan for the construction of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railways was drawn up by Sir Franklin Prestage, an agent of the Eastern Bengal Railways in 1878. The plan and estimates were submitted to the Government of Bengal which received the sanction of the then Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, Sir Ashley Eden in 1879. Arrangements were then made to form a company in order to carry out the endeavour. A sum of Rs. 14,00,000 was set aside for this purpose. This line is perhaps one of the first instances of an attempt at private initiative in railways. In 1879, the Darjeeling Steam Tramway Company was formed by Prestage and by the terms of a revised contract he was forced to scale down the line to a narrow gauge line (2ft/610mm). The name of the company was changed to Darjeeling Himalayan Railway Company in 1881 and the title was retained after it was taken over by the newly independent Indian state in 1948.

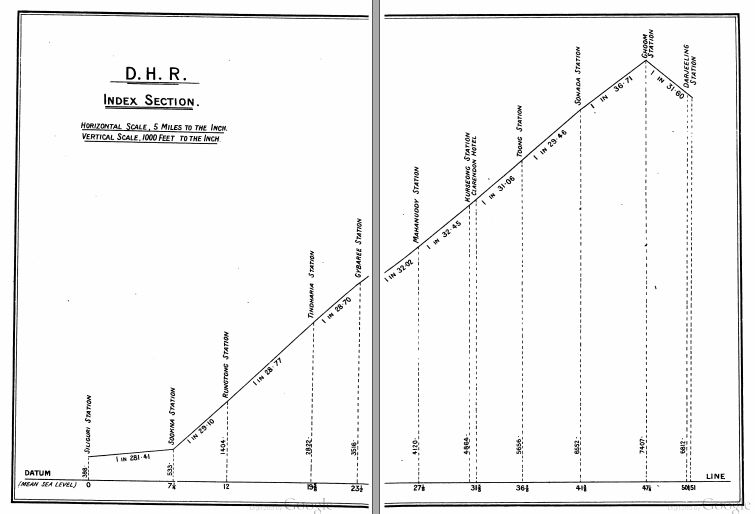

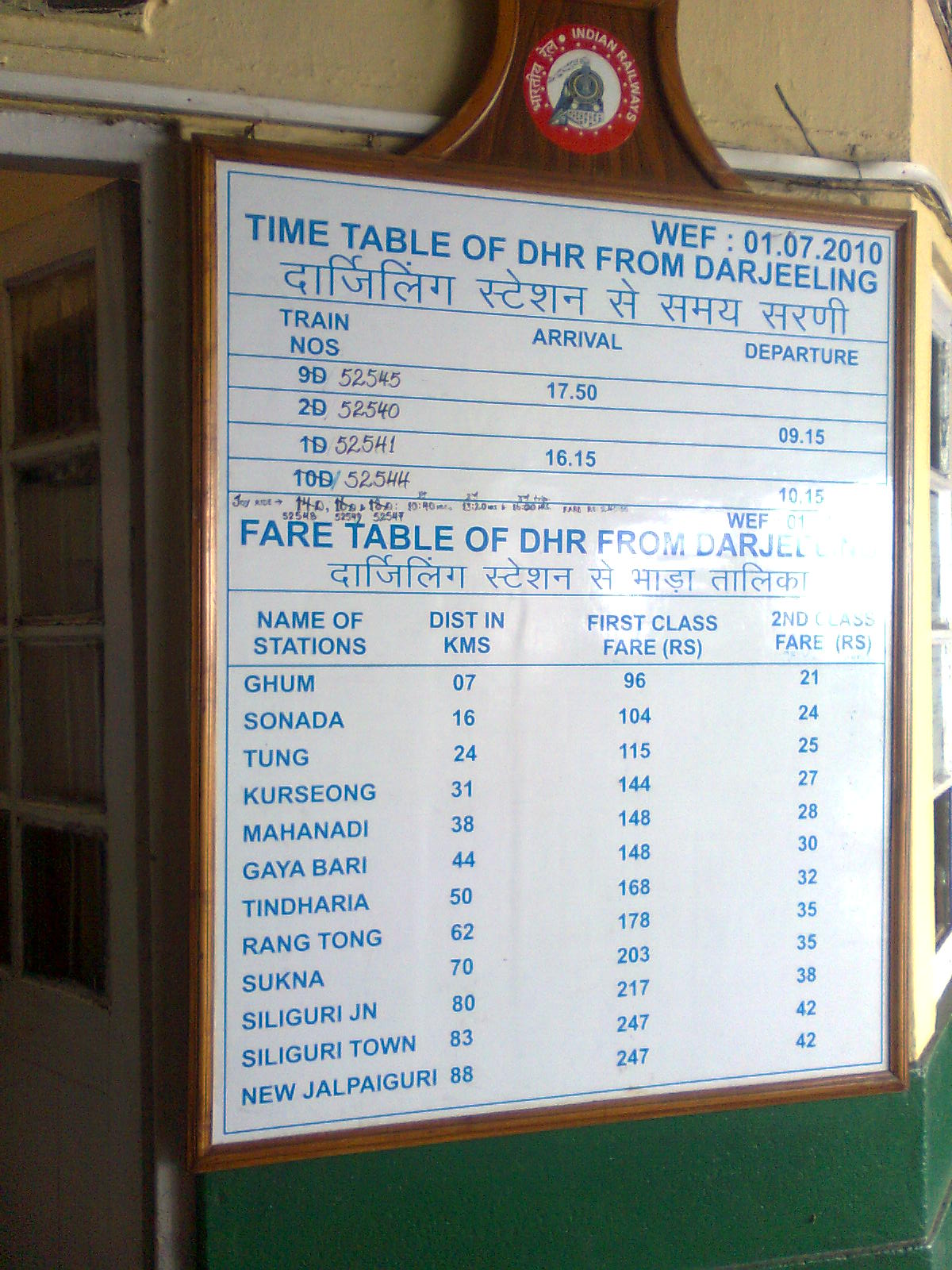

By the August of 1880, the line was opened for passenger and goods traffic for a distance of 32 miles from Siliguri to Kurseong which stood at 4,864 feet above sea level. The entire line was finally opened in July, 1881 with a total length of 52 miles till Darjeeling Bazaar.

A Railway Bridge along the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway Track,1890s. Source: Wikimedia Commons

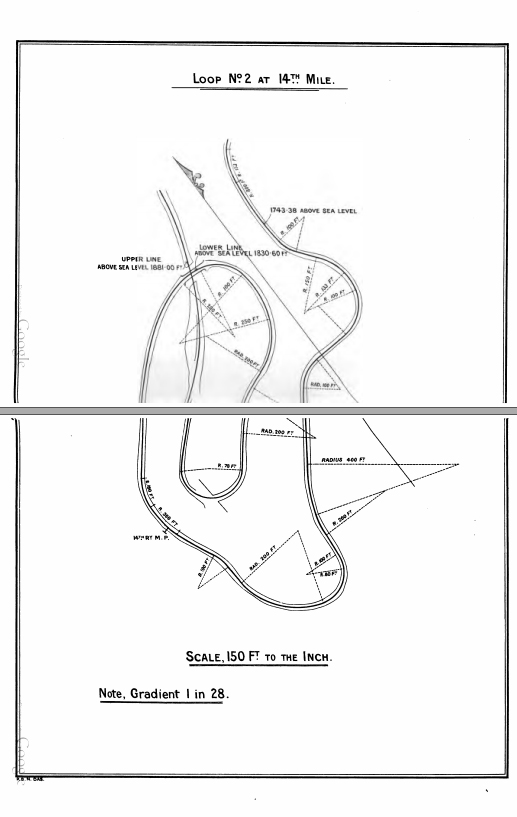

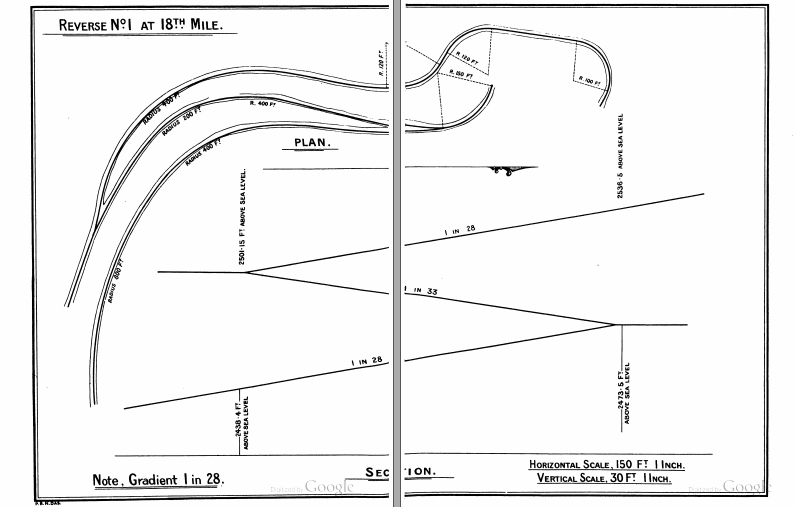

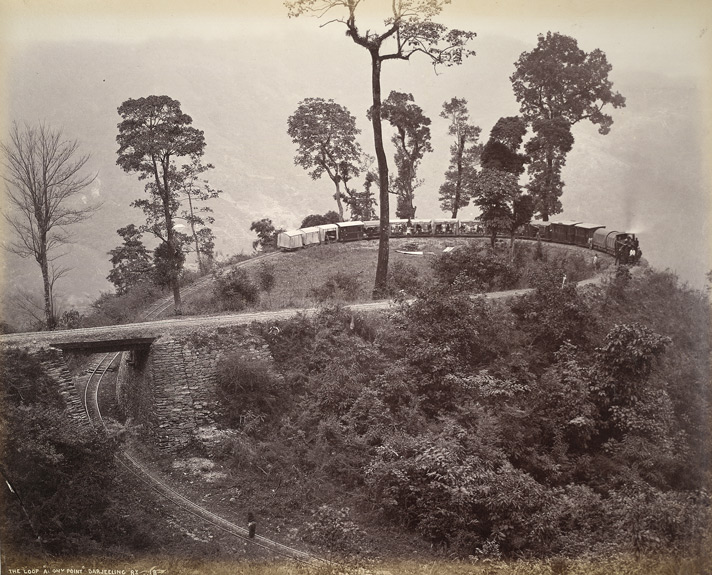

The total expenditure of construction stood at Rs. 31,96,000 or a cost of Rs.60.400 per mile. Many arrangements were made by the company to ensure a smooth service including the establishment of workshops for repairs.The gradients of the line were also improved to allow for high capacity engines to function on the line. Solid steel rails were laid on sleepers of timber and the locomotives were made by Messrs. Sharpe, Stewart and Company of Glasgow. They manufactured two types of locomotives for the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, one type weighing around 12 tons with hauling capacity of 39 tons in steep inclines and around sharp mountain bends and curves and the other type weighing around 14 tons with powerful brakes capable of taking a 50 ton train up sharp inclines. The steep nature of the mountain climb necessitated a lot of adjustments to be made at great cost, as a number of loops, spirals and reverses had to be constructed in order to navigate the steep ascent.

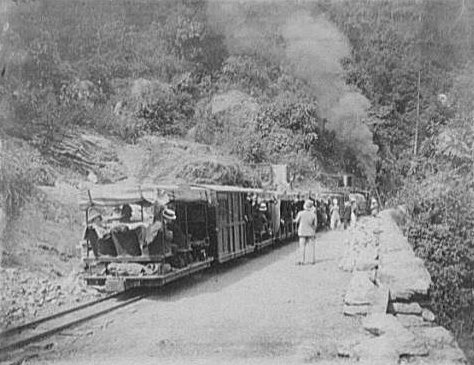

The Darjeeling Toy Train with Hooded Trollies in 1895. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The train had different carriages marked out to accommodate different classes of passengers. The First Class passenger carriages were 13 feet long and 6 feet wide and they were 7.5 feet high above rails with low floors. These carriages were fitted with 19.5 inch wheels and were divided into two compartments. The optimum carrying capacity of these carriages was 12 passengers along with small packages which could be kept under the seats. Though these carriages were suited for rainy weather they did not allow much opportunity for sightseeing. Open trollies would be attached to each passenger train and these would seat six first class passengers or sixteen second class passengers. These trollies were fitted with hoods and curtains and the passengers could take in the beautiful sights as they wended their way up from the foothills.

The baggage would be carried in separate trucks. Travellers were advised by the Eastern Bengal Railway through the pamphlet “Hints to Visitors” to carry extra clothing before leaving Siliguri for the hills to guard against the great temperature variation. Waterproof clothing was especially advised during the rainy months from June to October. They were advised to reach the station at least half an hour before the scheduled departure time. While ascending, a seat on the left side of the carriage was preferred so as to avoid the harsh afternoon sun, and to get views of the plains and to prevent giddiness brought on by the ever-shifting scenery of the hillside along with the decreasing levels of oxygen.

The Darjeeling Toy Train Boiler Engine, 1913. Source: Wikimedia Commons

On the Tracks of Time

So, what would a traveller’s journey on the DHR a century ago entail? The railway route which had been laid out first started its journey from Siliguri on level ground for around seven miles. The train would cross the Mahanadi River by a 700 feet long iron bridge and then offer the passengers a glimpse of the first tea garden visible on their journey, the Panchanai Tea Garden. The first stoppage of the journey would be at the Sukna Station which was around seven miles from Siliguri and from here the ascent to the hills would begin. Dense forest would greet the travellers and sometimes elephants would be sighted. The ninth mile would bring the travellers to the first sharp curves in the line. This point was considered to be a deadly place as many workmen engaged in construction work had succumbed to malarial fever. The first spiral or loop, a distinct feature of the line, would be encountered at the eleven and a half mile point. The loop was part of the engineering breakthrough which was undertaken to enable the line to overcome the steep gradients.

Between the twelfth and thirteenth miles the train would stop at Rungtong Stationfor cooling down and for water. From this point the line headed south towards another spiral and passed over a tunnel-like opening and then turned northwards and eastwards towards the third loop at the sixteenth mile.

Moving forward the next encounter would be with the “zigzag” or reverse at the seventeenth and a half mile, the first set of reverses, which was another unique feature of the line. This zigzag feature was styled on the backward and forward steps of ballroom dancing and had been suggested by Lily Ramsey, wife of Henry Ramsey, the chief contractor of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, as a way of navigating the gradients.

Map of Loop No.2 at the 14th Mile on the DHR route. Source: Illustrated Guide to Tourists to The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway and Darjeeling, 1896

Map of Reverse No.1 at the 18thMile on the DHR route.Source: Illustrated Guide to Tourists to The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway and Darjeeling, 1896

The Tindharia Station would be the second station on the hill line at the twentieth mile and here the Company had their locomotive workshops for repairs. From there the line would proceed towards another of the “zigzags” and the fourth loop at Agony Point.

Two more “zigzags” would be passed at the twenty-third mile at the Gayabari Station and at the twenty-fourth mile. At Pagla Jhora or “Mad Torrent” the halfway point of the journey would be reached. The train would thenstop at the town of Kurseong at an elevation of nearly 5,000 feet. Proceeding further, the Sonada Station at a height of 6,552 feet would be the next stop. The train would then pull up at the highest point of the line, the Ghum Station, at an elevation of 7,407 feet. From there the train would head downhill towards the town of Darjeeling. In 1919, the Batasia Loop was commissioned to counter the sharp descent, a fall of about 140 feet from Ghum to Darjeeling.

The Loop at Agony Point, Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The DHR Index Map. Source: Illustrated Guide to Tourists to The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway and Darjeeling, 1896

The train would finally come to a halt at the Darjeeling terminus providing the passengers with much needed reprieve.

Not much has changed of the DHR route in the present time and travellers on this mountain railway still make the same journey as their predecessors.

Train Stations of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

It could be, therefore, pointed out that, even though the scenery has drastically changed over the course of a century and the DHR gotten a diesel-powered heart transplant in 2000 with the NDM6 locomotives, the route continues to be the only connecting line between the past and the present.

The NDM6 Locomotive No.605 of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Government of Indiaa

Government of Indiaa

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.