Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

INTRODUCTION

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre marked a turning point in India’s struggle for Independence. A memorial was set up by the Government of India in 1951 at Jallianwala Bagh to commemorate the spirit of Indian revolutionaries and the people who lost their lives in the brutal massacre.

It stands as a symbol of struggle and sacrifice and continues to instill patriotism amongst the youth. In March 2019, the Yaad-e-Jallian Museum was inaugurated showcasing an authentic account of the massacre.

POLITICAL BACKDROP

The massacre of April 1919 wasn't an isolated incident, rather an incident that happened with a multitude of factors working in the background. To understand what transpired on April 13, 1919, one must look at the events preceding it.

The Indian National Congress had assumed self-governance would be granted once WWI ended but the Imperial bureaucracy had other plans.

WHAT LED TO THE JALLIANWALA BAGH MASSACRE

The Rowlatt Act (Black Act) was passed on March 10, 1919, authorizing the government to imprison or confine, without a trial, any person associated with seditious activities. This led to nationwide unrest.

Gandhi initiated Satyagraha to protest against the Rowlatt Act.

On April 7, 1919, Gandhi published an article called Satyagrahi, describing ways to oppose the Rowlatt Act.

The British authorities discussed amongst themselves the actions to be taken against Gandhi and any other leaders who were participating in the Satyagraha.

Orders were issued to prohibit Gandhi from entering Punjab and to arrest him if he disobeyed the orders.

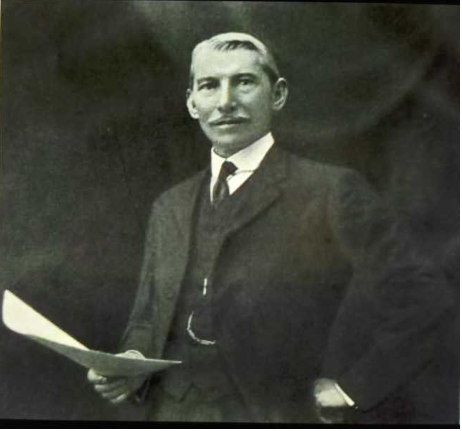

Sir Michael O’ Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab (1912-1919), suggested that Gandhi be deported to Burma but this was opposed by his fellow officials as they felt it might instigate the public.

Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr Satyapal, the two prominent leaders who were a symbol of Hindu-Muslim unity, organised a peaceful protest against the Rowlatt Act in Amritsar.

On April 9, 1919, Ram Naumi was being celebrated when O’ Dwyer issued orders to the Deputy Commissioner, Mr Irving to arrest Dr Satyapal and Dr Kitchlew.

The following extract from the Amrita Bazar Patrika, dated 19th November, 1919, talks about the witness account of Mr Irving in front of the Hunter Commission and highlights the mindset of the British authorities:

“He (Irving) was directed by the Government of Sir Michael O’Dwyer to deport Dr Kichlew and Satyapal. He knew that such an act would lead to a popular outburst. He also knew that none of these popular leaders favoured violence. He invited the two gentlemen to his house on the morning of April 10th and they unsuspectingly responded to the call no doubt relying on his honour as an Englishman. But after they had been under his roof for half an hour as his guests, they were caught hold of, and removed towards Dharmasala under police escort! Mr Irving told this story without showing any sign of having done an act which very few Englishmen would care to do.”

On April 10, 1919, the infuriated protestors marched to the Deputy Commissioner’s residence to demand the release of their two leaders. Here they were fired upon without any provocation. Many people were wounded and killed.

The protestors retaliated with lathis and stones and attacked any European who came in their way.

One of the mishaps was the attack on Miss Sherwood, Superintendent of the Mission School in Amritsar. As per her testimony, on April 10, 1919, she was intercepted and beaten by a mob which screamed “Kill her, she is English” and “Victory to Gandhi, Victory to Kitchlew”. She was attacked until she fell unconscious. The mob went away assuming she was dead. However, a counter-narrative is provided by the 'Lokasangraha', a weekly published out of Bombay, which denies claims of severe harm, stating instead that the wounds inflicted were infact minimal.

APRIL 13, 1919 - JALLIANWALA BAGH MASSACRE

After passing the Rowlatt Act, the Punjab Government set out to suppress all opposition.

On April 13, 1919, the public had gathered to celebrate Baisakhi. However, the British point of view, as seen from the documents present in the National Archives of India, indicates that it was a political gathering.

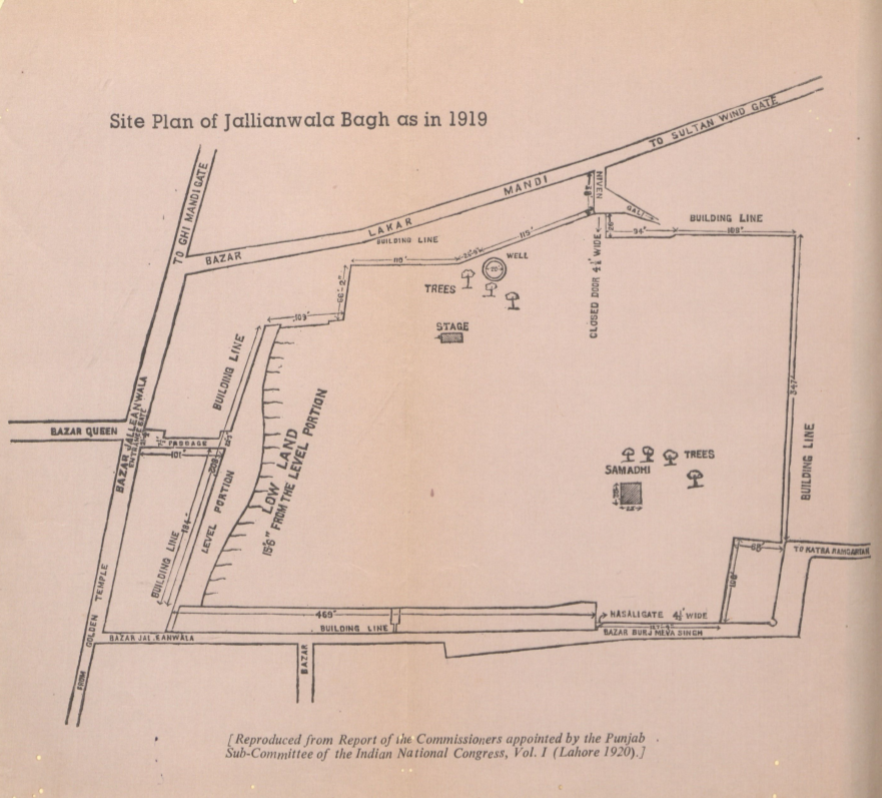

Inspite of General Dyer’s orders prohibiting unlawful assembly, people gathered at Jallianwala Bagh, where two resolutions were to be discussed, one condemning the firing on April 10 and the other requesting the authorities to release their leaders.

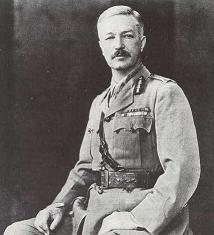

When the news reached him Brigadier-General Dyer, headed to the Bagh with his troops.

He entered the Bagh, deployed his troops and ordered them to open fire without giving any warning. People rushed to the exits but Dyer directed his soldiers to fire at the exit.

The firing continued for 10-15 minutes. 1650 rounds were fired. The firing ceased only after the ammunition had ran out. The total estimated figure of the dead as given by General Dyer and Mr Irving was 291. However, other reports including that of a committee headed by Madan Mohan Malviya put the figure of dead at over 500.

POST JALLIANWALA BAGH

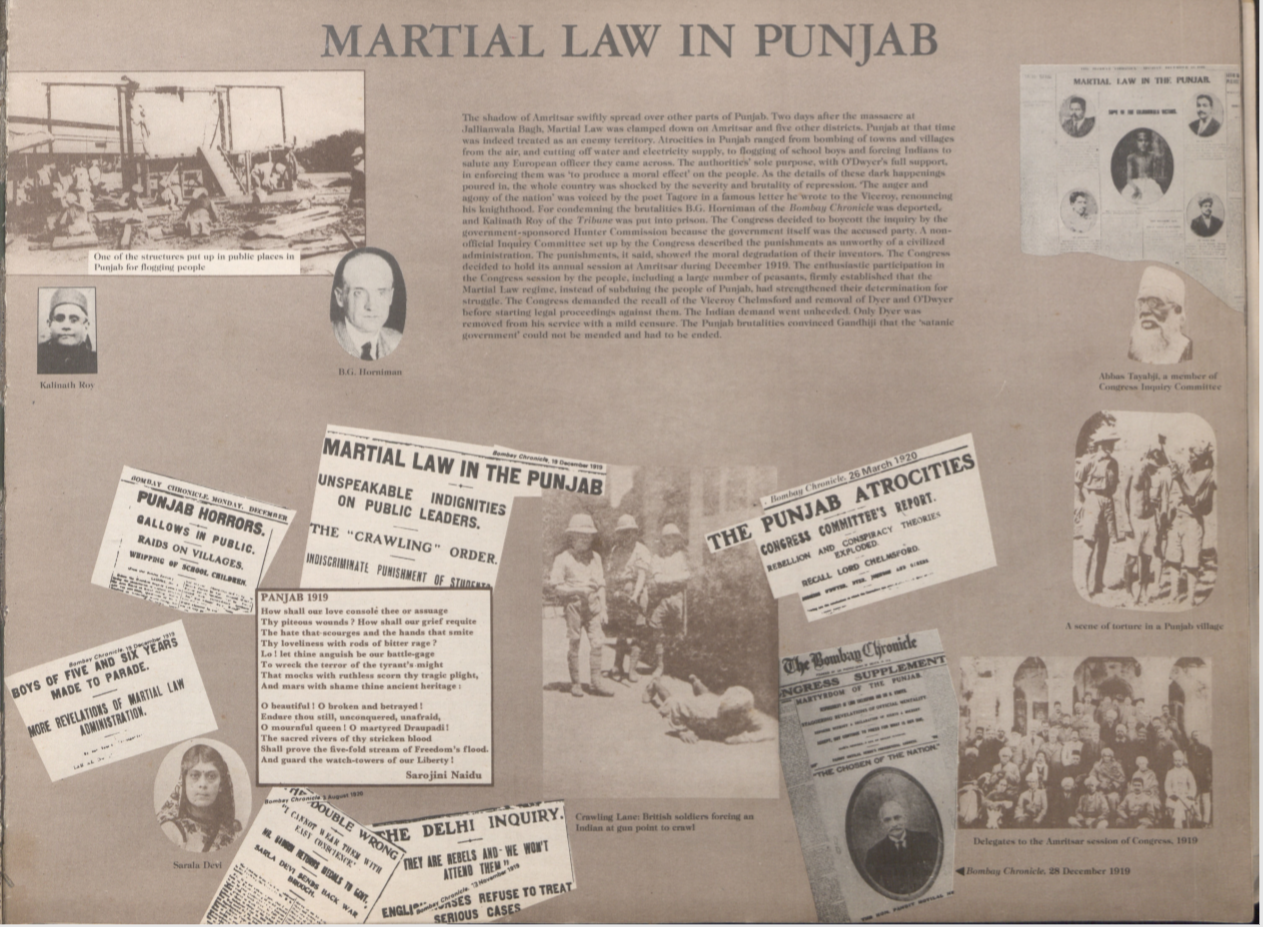

Two days after the massacre, Martial Law was clamped down on five districts - Lahore, Amritsar, Gujranwala, Gujarat and Lyallpore.

The declaration of Martial Law was to empower the Viceroy to direct immediate trial by court-martial of any person involved in the revolutionary activities. As the news of the massacre spread across the nation, Tagore renounced his Knighthood.

HUNTER COMMISSION

On October 14, 1919, the Disorders Inquiry Committee was formed to inquire about the massacre. It later came to be known as the Hunter Commission.

The Hunter Commission was directed to announce their verdict on the justifiability, or otherwise, of the steps taken by the government. All the British officials involved in the administration during the disturbances in Amritsar were interrogated including General Dyer and Mr Irving.

The following extract shows Dyer’s unapologetic attitude towards the massacre:

Question - After firing took place, did you take any measures to attend to the wounded?

Answer - No, certainly not. It was not my job. Hospitals were open and they should have gone there.

General Dyer’s actions on the day of the Massacre received a prompt acknowledgement from Sir Michael O’ Dwyer who at once wired to him: "Your action correct. Lieutenant-Governor approves.” Both Dyer and Dwyer faced violent criticism from various newspapers who gave their own accounts of the brutal massacre.

Extract from the Independent, Allahabad, dated 21st November 1919I fired and fired well. No other consideration weighed with me” said Dyer.

The evidence General Dyer presented before the Hunter Committee stood as a confession of the brutal act he committed.

The Committee indicated the massacre as one of the darkest episodes of the British Administration.

The Hunter Commission in 1920 censured Dyer for his actions. The Commander-in-Chief directed Brigadier-General Dyer to resign from his appointment as Brigade Commander and informed him that he would receive no further employment in India as mentioned in the letter by Montagu to his Excellency.

O’ DWYER’S ASSASSINATION

On March 13 1940, at Caxton Hall in London, Udham Singh, an Indian freedom fighter, killed Michael O'Dwyer who had approved Dyer's action and was believed to have been the main planner.

Gandhi negated Udham Singh’s action and referred to it as an "act of insanity". He also said, “we have no desire for revenge. We want to change the system which produced Dyer.”

Thus, Jallianwala Bagh was the initial spark that led to the Independence of India. It was a tragedy for both the sufferers and the colonial rulers. It revealed a fatal flaw in their assumptions and attitude. Eventually, it led to their departure from the land which they had hoped to rule for centuries.

Government of Indiaa

Government of Indiaa

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.