Lothal

Lothal is the name of the ancient mound situated in the revenue jurisdiction of Saragwala Village in Dholka Taluka of Ahmedabad District, Gujarat. The word ‘Lothal’ meaning ‘place of the dead’ in Gujarati is said to have been derived by combining the words Loth and thal (sthal).

The Site

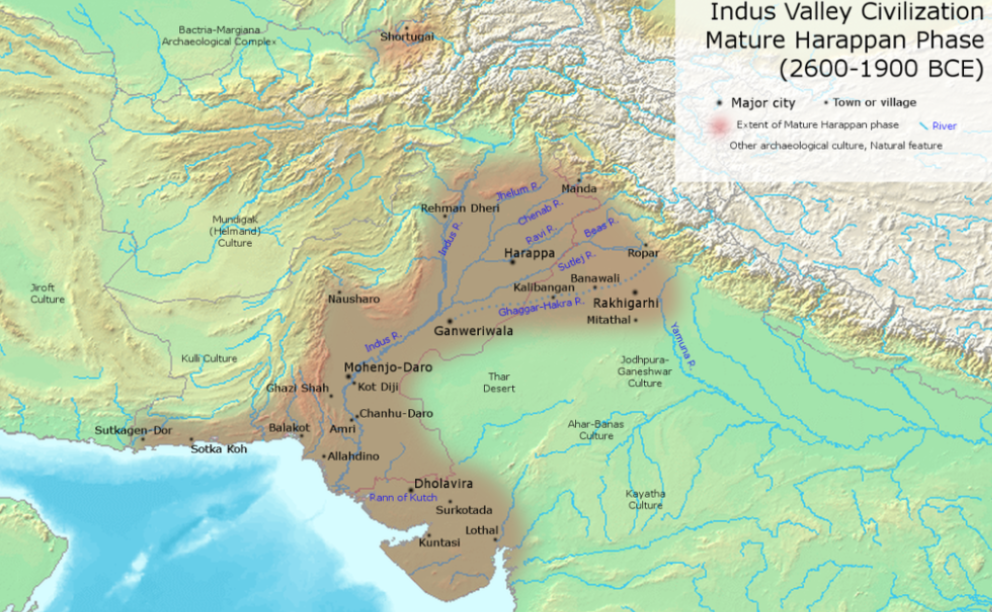

In the 1920’s Sir John Marshall excavated the major towns of the Indus Valley Civilisation, namely Harappa and Mohenjo-daro. Indus Valley came to be known as the cradle of all ancient civilisations. It was some years later in 1952, when archaeologist SR Rao of the Archaeological Survey of India discovered the sites of Lothal, Kalibangan, Dholavira and Rakhigarhi in a newly independent India.

Though 18 times smaller than the nodal sites of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa that are now in Pakistan, Lothal is important because it is India’s first Harappan site. Before the establishment of the Harappan Civilization circa 2400 BCE, Lothal was a small village perched on the eastern flank of the river providing access from the hinterland to the Gulf of Cambay. It is one of the oldest port towns with an operating dock system in the world.

Map of the Mature Harappan Civilization

Source - Wikicommons

Lower town excavation, 1961

Source - ASI Images

Planning

Lothal was planned in such a way that the primary concern was to ensure the safety of the town from the annual sheet flooding and high-intensity flash floods. Houses were built on terraced platforms and further safeguarded by a peripheral wall. The entire town was divided into several blocks of one or two-meter high platforms of sun-dried bricks.

Each platform served as a common plinth for a group of twenty or thirty houses.

The IndusValley civilization paradigm paradigm of dividing the city into a citadel or acropolis and a Lower Town was followed in planning Lothal. The Ruler and his entourage lived in the acropolis where houses were built on 3m high platforms and were well equipped with all civic amenities including paved paths, underground drains and a well for potable water.

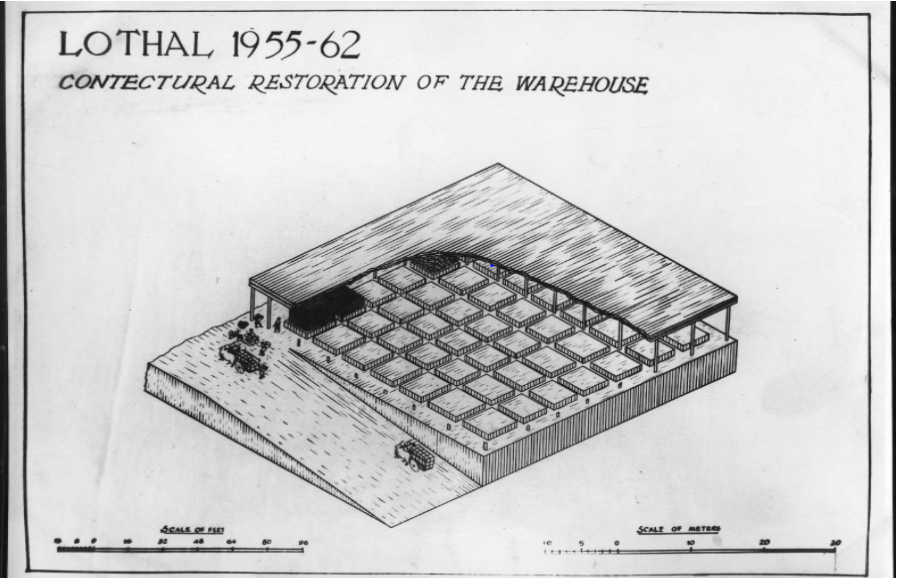

The Lower Town also enjoyed the civic amenities and was subdivided into two sectors. The north-south arterial street consisted of the main commercial center, which was flanked by shops and the houses for the rich merchants and craftsmen. The residential sector lay to the east and west of the commercial block. It is obvious that while planning the town of Lothal, the makers accorded high priority to two features - The first feature was the dock for berthing ships and the second was space for warehouses where cargo was stored and examined. The dock was built on the Eastern flank of the town with great precision. It was located away from the main current which helped avoid silting but ,at the same time, it gave the ships access to the dock during high tide. The warehouse was built close to the acropolis on a podium of mud-bricks so as to serve as a clearinghouse for incoming and outgoing cargo. Its location enabled the Ruler to supervise the movement of the ships in the dock and the transactions of the warehouse simultaneously.

The arterial streets running in cardinal directions and connecting various blocks were intersected by lanes which provided access to individual houses. The underground and surface drains built of kiln-fired bricks ensured quick disposal of sullage and stormwater.

Lothal Port Warehouse, 1955-56 excavation bluprint

Source - ASI Images

Urban Systems in an Ancient Civilization

The Harappan Civilisation was characterized by its clear organization, skilled architecture and civic sense. It contributed to the introduction of a uniform system of weights and measures, strict trade regulations, efficient municipal administration and standardization of goods and services to facilitate large scale production. Industrial goods were produced from imported raw materials such as copper, chert and semi-precious stones at urban centres like Mohenjo-daro and Lothal and later distributed in smaller towns. Similarly, agricultural products were funnelled to urban centres where they were used as a form of payment. It is also said that Lothal had no encroachment of public streets and the width of all the roads were standardised over the years. Services for unclogging of public drains and cesspools were also established. The main sewers were joined by runnels discharged into the dock where the waste was washed away by the tides.

Throughout their vast civilisation that extended from present-day Iran and Afghanistan up to Kashmir, Delhi and South Gujarat, standard stone weights and seals, copper celts, spearheads, jewellery, toys and pottery were in use. The architectural planning was very similar across the Harappan civilisation.

The homogeneity of Harappan products is often mistaken for conservatism which is said to be responsible for the decay of the civilisation.

The World’s Oldest Dock

With the birth of a planned Harappan port town in 2350 BCE, Lothal enjoyed immense prosperity through foreign trade. It became a busy industrial centre which imported pure copper and produced bronze celts, fish hooks, chisels, spearheads, and ornaments that were then supplied through trade channels all over the Western Province. Another industry which catered to domestic needs was the stone blade industry. Fine chert was imported from Sukkur Rohri in Sindh or present-day Bijapur district in Karnataka.

export oriented industries were that of bead making and shell working. Bhagatrav supplied semi-precious stones while a chank shell came from Dholavira.

Religion and Burial Systems

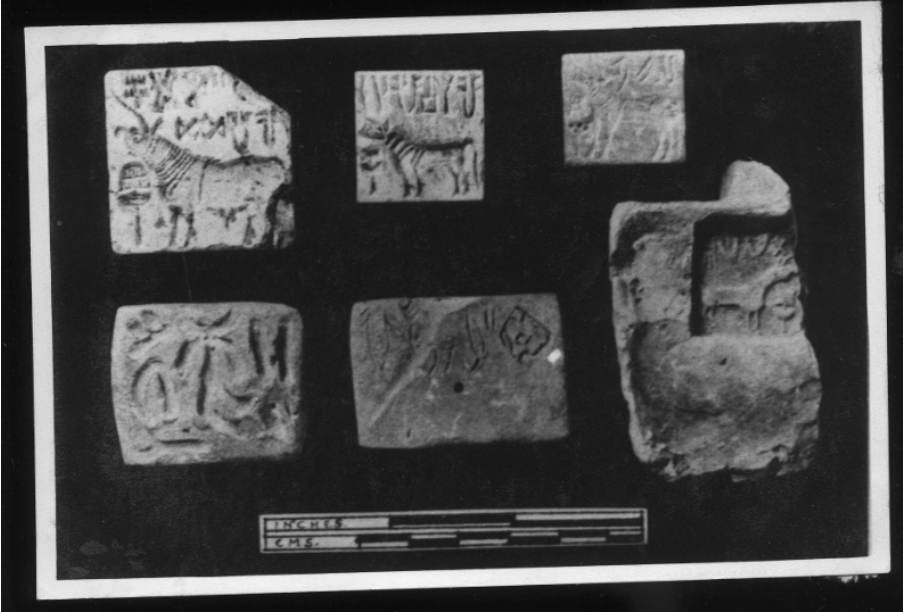

The fire-altars found in houses and public places at Lothal and Kalibangan indicate that the Harappnas worshipped the Fire-God. The horned deity engraved on three Indus seals under the arch of flame can mostly be identified with the Fire God.

The animals depicted on the seals are symbolic of the various animal deities revered by particular groups of people. What is interesting is the conspicuous absence of the veneration of the Mother Goddess (otherwise popular throughout the rest of the Harappan Civilisation.) The varying religious practices through the entire civilisation can thus be understood.

The cemeteries at Lothal had a unique system of joint-burials in which two individuals were buried simultaneously. There was also the regular burial system, with a single body for every grave, but the joint-burials were unusually practiced in cases of family calamities or couple mishaps. Along with the dead, they also placed pottery, beads of shell and copper in the graves.

Joint burial in Lothal, 1961 excavation

Source - ASI Images

Art and Metallurgy

The bead-making industry of Lothal was famous for its micro-cylindrical beads of steatite. Twisted strings of several strands of microbeads of steatite would make attractive necklaces, bracelets, bangles and waistbands. The Harappans loved beads of every conceivable material ranging from gold, copper and gemstones to shell, ivory, bone and clay.

The most distinctive seal of the mature Harappan Culture is the seal made of steatite. Occasionally copper, shell, agate, ivory, faience and terracotta were also used for making different seals. Lothal yielded two hundred and thirteen seals and sealings which are unique representations of glyptic art, that display intricate calligraphy and realistic rendering of animal motifs. The unicorn is, no doubt, the most popular motif in all the Harappan sites but the humped bull with long horns and flowing dewlaps is the most beautiful animal carved on the seals. The bull, rhinoceros and buffalo do not, however, occur on Lothal seals. Short-horned bull, mountain goat, tiger and some composite animals were more to the preference of Lothal seal-cutters. In addition to the wide range of animals, there also is a short inscription in intaglio on almost all seals.

Steatite seals, 1955 excavations

Source - ASI Images

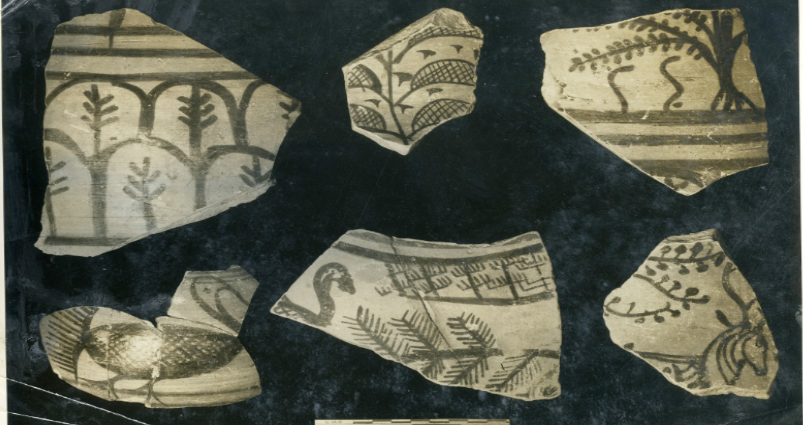

Painted potteyware from Lothal with signature flora and fauna designs.

Source - ASI Images

One of the major factors that contributed to the urbanisation of Harappan settlements was the abundant supply of metals. Lothal imported bun-shaped ingots of copper of 99.81% purity from what archaeologists presume was the area that is presently called Oman. The smiths at Lothal were known for mixing tin with pure copper in differing ratios so as to make the desired weaponry. The iconic bronze Harappan figure, the Dancing Girl was an example of great metallurgy by the master-smiths at Mohenjo-daro and Lothal.

Historians DD Kosambi and Romila Thapar quoted pottery and ceramic art as one of the characteristic features of any ancient civilisation. The Harappan Civilisation had its distinct form of pottery and ceramics, with Lothal being the largest centre of its production. The Harappan vessels generally were sturdy, well fired and often painted red or black. Lothal had two unique forms of pottery. The convex bowl with or without the stud handle in micaceous Red Ware. Lothal artists followed the ‘realism’ style of painting their pottery. These designs showed animals in their natural surroundings with a lot of focus on flora.

Decline

The decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation has been a matter of debate for a very long time amongst the scholars of historical studies. With the Harappan script undeciphered till date, the debate has only magnified with many different theories being discussed. The decline of Lothal is usually associated with the coming of a flood of great intensity that submerged the entire town. The mud-brick houses were raised to the ground and the massive walls and platforms were heavily damaged. Most of the streets through which flood waters gushed were filled with loam and debris. Some also predict the crumbling economy of Lothal by 1900 BCE, that led to the loss of jobs and livelihoods. Lothal, much like the entire civilisation succumbed to a natural calamity, that marked the end of the world’s first river civilisation.

Government of Indiaa

Government of Indiaa

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.